Before building (or buying!) a training manual for a veterinary hospital, think about what you’re ultimately training, who you are training, and how students best learn.

They got a manual, a checklist of things they were supposed to know, and four weeks of training from three different team members. So why is it that these employees are still not doing anything right?

There are tens-of-thousands of training manual pages spanning the fifty thousand or so veterinary practices in the U.S., yet many managers fret that they do little good. The more cynical contend that, despite all the effort, most of them are never read. They grumble that instead of tools of learning, they are used as wedges to keep tables from wobbling, as liners for the insides of employee lockers, or as height-assists to grab out-of-reach pill bottles…and the wrong bottles at that!

Training Starts at Hiring

Your training is not going to land with all individuals. Firstly, learners have to come to the table able to learn; they have to come to the classroom rested, fed, drug and alcohol free, and supported socially by family and friends. Unfortunately, in the veterinary world, even these basic requirements are not met by all applicants. People lacking these fundamental underpinnings often flock to the veterinary world for the unconditional love they can get from pets. While I’m glad that many of them have found meaningful employment with us, experience has taught me they have trouble delivering a consistent performance. That shortcoming is not reflective of my training skills; but my inability to hire with my head instead of my heart.

Secondly, students are never really turned on by a learning experience unless three criteria are met:

- Students have to have an underlying interest in the material. Failure to teach a first-year veterinary student how to be an excellent customer service representative isn’t a training failure, it’s a hiring failure. Afterall, she didn’t go to vet school because of her passionate desire to answer phones.

- Instructors have to want to help their students. They have to like and be curious enough about their charges to identify learning strengths and interests in the individual, and then target education to those areas.

- Teachers have to know how to engage students in the material. Through group work, apprenticeship, and real time learning, wise teachers don’t just expose the students to learning, they immerse them in it.

Training that Taps into Intrinsic Motivators

Great training programs focus on goals and the student’s strengths and interests. They find a way to connect what needs to be done to what employees already want to do.

Starbucks is a great example. Starbucks needs people to handle cash, run registers, steam milk, grind coffee and dozens of other tasks, but more importantly, they want employees to complete these tasks as an extension of deeper intrinsic motivators. Starbucks articulates these motivators as a pocket-sized version of their mission, three pillars that they identify as Personalize, Connect, and Uplift.

Think how this extra step, the process of thinking about what needs to be done as well as how and why it should be done, informs the hiring process. It begs leaders to think more deeply about a candidate’s work and life experience, the kinds of questions hirers should ask during the interview, and the kinds of responses that point to the better candidate. When you hire for mission, you stack the deck with employees that can learn and want to learn what you have to teach them.

Intrinsic (Pull) versus Extrinsic (Push) Motivators

There are some things we are drawn or pulled to do, while we do other things because we were pushed. We call these two groups of motivators intrinsic and extrinsic.

Extrinsic motivators motivate us with things like prizes, cash, free lunches, or tickets to a sports game. Intrinsic motivators reside internal to us and motivate us with things like personal growth, a feeling of accomplishment, winning affirmation from the group, and so forth.

Of the two, intrinsic or ‘pull’ motivators are the ones that motivate the strongest and for the longest period of time. Here are two examples. It’s September 28th, rent is due in a few days, and you are seriously short. Today you don’t feel like going to work, but you go anyway because the rent deadline pushes you to get out of bed. Alternatively, it is September 28th and you don’t feel like going to work, but you think about your friends at work, how much they enjoy your company and you theirs. You also remember that today is supposed to be especially busy and you don’t want to leave them in the lurch. You are pulled to get out of bed because of your strong affinity for your coworkers and what they mean to you.

Here’s another example. Think about the things we need a veterinary hospital manager to do:

- Manage operations

- Professionally lead day-to-day activities

- Ensure excellent patient care, etc.

Now explore the same goals, but this time, write them in a way that invites action, not a way that commands it.

- Look at the practice through the eyes of a client.

- See and hear management through the eyes and ears of an employee.

- Know what it’s like to walk in the pads of one of our patients.

The second description doesn’t push the applicant to work, it pulls. It doesn’t hire and then train skills; it identifies skills and then hires. It stokes the applicant’s interest and engagement weeks before training begins.

Successful training begins with successful hiring; it’s as much about the students in the seats, as the books on the desk.

Veterinary Student Insight

I recently worked at a large referral hospital and observed the interns during their rotation: two weeks in radiology, two weeks in cardio, two weeks in surgery and so forth. In each service, students experienced a different set of teaching styles. In one service, the teacher started the day with rounds. Each student had to stand in front of others and present their case to the rest of the professionals in the room. In another rotation, students followed the professor through the day’s casework and were peppered with questions at every turn, “Kevin, which leg do you believe the horse is favoring? Evelyn, in this case, what do we need to think about if we know the patient has been on long-term NSAID use?”

But what was most interesting were my interviews with the students regarding their learning experience. In every case, students told me that their learning was predicated on their relationship with their teacher and the time they had working inside their rotation on specific cases, not on the instruction they received.

I found this illuminating. Some professors put a lot of time and effort into their lesson plans: testing students’ knowledge, structuring daily rounds, and so forth, but that was not identified by the students as the major driver of learning. It was the immersion in the work and trust in the advisor that students felt had the most impact on their learning experience.

It’s also worth noting that the accomplished people that end up in my leadership classes rarely tell me that they experienced structured, on-the-job training in their professional lives. When I ask them how they were trained to do their work, they shout out things like. “I wasn’t trained. I was thrown into it! Sink or swim!” Is this evidence that one way to teach a person to swim is to half drown them under water?

Teacher-versus-student centered learning

Teacher-centered learning is instruction where teachers are the main authority figure and the students are empty vessels into which the teacher pours knowledge.

Student-centered learning is instruction where the students’ interest in the material drives the learning experience and where the teacher is more in the background as a source of safety and support as needed.

There is a lot of research (and contention!) as to which teaching style works best. I’ll leave you to do your own research on the topic, but I’ll share several observations:

- Teaching-centered learning sounds like a good idea, but it’s predicated on having a teacher handy to do the educating. Usually in veterinary hospitals the teachers, really our most experienced employees, are too busy doing the work of receptionists and techs to also work as teachers.

- Teaching-centered education requires enough time to complete the syllabus, time that we usually run out of long before we’re done.

- In most practices, client care representatives are given teacher-centered learning. That is, they are handed a manual or a list of skills they must master, and then they are methodically guided through the list until they’re fully trained (or someone quits and they are thrown into the job). Assistants, on the other hand, are usually provided student-centered learning. They follow more experienced team members around, watch tasks repeated over and over, and then begin to participate in the work they like best or that seems most natural to them.

Of the two cohorts, I believe assistants learn faster. As a bonus, it appears they learn the material in the broader context of the overall client and patient experience. I wish more managers allowed receptionists the same chance to rotate with technicians and doctors through the service experience. I think they would enjoy their education more, learn better, and bond with more employees.

Training Methods Best Suited for Veterinary Hospitals

Lean on Artificial Intelligence

Artificial Intelligence is accelerating so quickly that even the concept of training programs as we know them is becoming obsolete. Today, Open A.I. knows everything you know about veterinary medicine and more. It also understands how to do most of what you know how to do in a hospital and many things you don’t. To illustrate, use this link to go to ChatGPT (it may require you to create an account first) and ask the tool the following questions:

- What should I do when a client calls my veterinary hospital and tells me her dog has diarrhea?

- How do I run maintenance on my Idexx LaserCyte machine?

- What is the proper way to wrap a veterinary spay pack?

- What instructions should a client follow when dropping off a cat’s urine specimen?

Impressive, right? Now ask ChatGPT to:

- Outline a veterinary hospital training manual

- Identify the chief OSHA hazards for your OSHA-required Tour of Hazards

- How to book a client using Avimark.

As you can see, our efforts to outline, construct and even teach a veterinary training program seemly laughably puny to what artificial intelligence can do. Everything that has ever been written about veterinary medicine and published on the World Wide Web is instantly accessible to artificial intelligence systems. Already, there are secondary companies in the business of building application program interfacing systems (APIs) that can connect these large pools of information (ChatGPT, WatsonX, Google A.I., et al.) to your local data base to personalize your training or customer service programs.

In the past year, artificial intelligence has deflated the value of the experience and knowledge we leaders first brought to our hospitals. The all-star managers of the future won’t be the ones with the most years in the biz or the most knowledge, but the ones that can find ways to leverage the power of A.I. to train team members throughly, efficiently, and cost effectively.

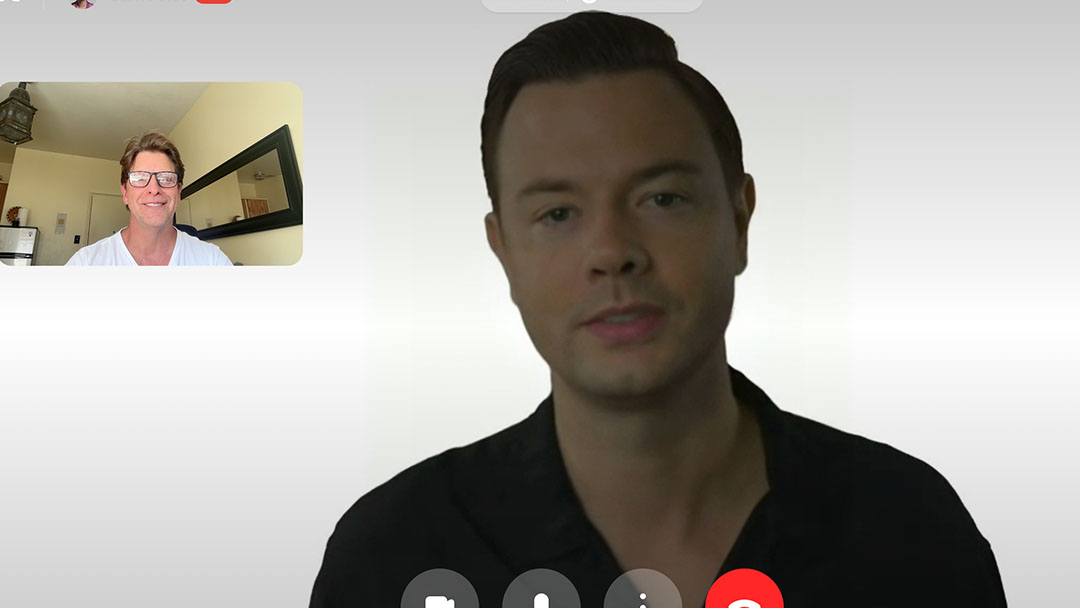

Bash Halow discusses training with a digital clone, a kind of chatbot designed to mimic a real person’s voice, gestures, thoughts, conversation style, and even humor. Once interfaced with an artificial intelligence source like ChatGPT or Watson, these clones can bring an entire internet of knowledge to any conversation and customize it to the person to whom they are speaking. It’s unimaginable that digital clones won’t be teaching training (and other!) classes across the globe in the next 1-2 years.

Apprenticeship

If you are lucky enough to hire an individual who is genuinely interested in the business of service, care, and medicine and in whom you see promise, the best way to train is using the apprenticeship method. Having the new employee work alongside a role-model technician or doctor through a process like outpatient care gives the student a finite set of skills to watch and learn. It also exposes him or her, in a very short time period, to many core competencies:

- Animal restraint

- Vaccines

- Parasite prevention and testing

- Common outpatient diseases

- Euthanasia, etc.

When paired with the right individual, apprenticeship teaches skills and culture. It teaches what to do, how to do it, and how to behave while doing it.

Micro-lessons

Microlessons work better than long, dragged out meetings. Stay on the lookout for 5-or-10-minute lulls in the day’s schedule, gather all nearby team members, and teach one skill. A variation on this theme is to use the morning huddle, a brief meeting at the start of each day, as a way to impart one nugget of learning to everyone assembled.

Using existing online resources

AtDove is just one of many online veterinary training programs and one of my favorites. This subscription-based platform offers lessons in every imaginable topic of veterinary nursing as well as an extensive section on customer care. Having a roster of online learning means that team members can learn whether or not in-house trainers have the time to teach.

On-Your-Feet Lunch and Learns

Lunch and learns are great, but in my experience, it’s hard to hold employees’ attention through all that chewing and sandwich paper unwrapping. I think it’s better to get people up on their feet, minus the Panera, working in groups, and walking through whatever skill you would like them to learn. Walking through the skill, rather than sitting around and talking about it, stimulates more thought and is generally more energizing. Group work is also closer to what the real-life experience is like. Exploring skills with others helps individuals not only learn the skill, but learn how it should be optimally completed in the company of fellow employees.

Managing Failure

If you’re reading this, you are likely one of the team members that your hospital leans on for autonomous, nimble, adaptive decision making. They lean on you for this strength because almost nothing in our line of the work is text book. Each client, patient, and predicament comes with its own unique set of needs and concerns and figuring out what’s best requires critical thinking that takes into consideration a myriad of variables.

How is that you came to possess this precious set of skills? Many of you would answer ‘experience’, but I would argue that it was more specifically a mixture of time on the job, training, failure.

Mistakes make for forceful instructors. They can be unforgiving, shaming, intense, unforgettable, and highly effective at teaching. They’re also a pathway to a deeper understanding of our work, autonomy, a lesson in the value of what we do and how, and a cause for bonding between employers and employees, that is if they are managed properly.

Because mistakes in our business can literally lead to death, we often come down hard on those that fail. This is a mistake in itself. Because of the dangers inherent in our work, we need to protect patients, clients, and ourselves, but not at the expense of encouraging proactiveness and problem solving. We need to find the right balance between risk and reward, practice and perfect,

Talk to your team about their reaction to others’ mistakes. If you’re going to create a team of strong performers, your entire hospital has to think of mistakes more like a rite of passage, and less like a grade of performance. When team members fail, we have to stop blaming them about the outcome and support the fact that they tried. With enough exposure to successful, seasoned team members they can figure out how to arrive at the right solution, but they’ll never get there if we’ve first snuffed out their willingness to try.

Conclusion

Though we’d like to live in a world in which employees are trained from start to finish and graduate ready to take on the rigors of practice life, such a system doesn’t work for the majority of us. Wrong hires, a lack of time, and an ineffective approach to learning are all working too hard against us. For better success, hire individuals eager and able to learn what you want to teach, play to their learning strengths, nurture trust, and work inside time constraints to achieve your learning objectives.