Addressing angry clients, talking to grieving pet owners, telling an employee that it’s time to go… swallow that lump in your throat. Let’s get these difficult discussions right by remembering the essential elements of managing loaded convos.

Reflect on Your Goals

Emotions are high. Your stomach is in knots. The other party appears primed to lose her temper. Remind me again why we are about to walk into this lion’s den? It’s important that we reassess what our objectives are before entering the room if we are to emerge on the other side of this discussion better off than when we walked in.

If your goals are to blame, blow off some pent up steam, or try to underline how bad the other party made you feel, then you’re better off not walking into the room at all. That’s not a way to start a conversation, it’s a way to strain it. You’re more likely to be pleased with the outcome if your goals are in any of the following silos:

- Set boundaries: No shame, no blame. As a steward of your business’s culture, it’s your job to underline what is and is not acceptable behavior. Having a meeting where you respectfully articulate expectations, and then help the individual troubleshoot any behavioral issues, is a good thing.

- Learn about the problem: Nearly every client exchange and employee action is part of a bigger series of actions by the whole team. To finger one person as responsible without looking at how workflow protocols and other team members actions contributed to the matter means that you’re always going to come up with a less-than-comprehensive solution. Go into the meeting eager to create a space for a safe exchange of information and to learn.

- Grow Trust. Sitting down with members of your team, showing interest in their perspective, and working with them to improve strengthens trust. Finding a way to demonstrate your empathy for a pet parent (or for their pet!) is also a lead-in to trust. Played right, this ‘difficult’ meeting could be an opportunity for you to show that you genuinely care and grow the bond that the two of you share.

- Underline that this meeting is important. You may be interested in underscoring the gravity of the situation. Setting time aside to speak to someone in a room where you will not be interrupted underscores that this topic is potentially critical to the future of your relationship together.

Goals like these are specific enough to shape your mindset, but not so rigid that they prevent you from being open to hearing and learning new information. They’ll help you sidestep your urge to be combative and train your sights on relationship growth.

Client and Co-worker De-escalation Training for Your Team

Your employees should learn how to de-escalate heated client and coworker situations as part of their OSHA safety training. De-escalation training by Halow Consulting can usually be fully funded! Find out how you can bring this valuable, important lesson to your team. Click for more info

Setting The Stage: Place and Body Language

Place

Choosing a quiet location where you won’t be interrupted signals to the other party that they’re worthy of your undivided attention. It can also signal that the stakes are high, an important message that you may want to send an employee or client when the relationship is at risk of ending. Remember while your office is a comfortable space for you, it may be intimidating to others who may feel as though they are being called into enemy territory. Lastly, it’s a sorry state of affairs to have to worry about this sort of thing, but think about safety. If the discussion gets out of hand, will there be someone within earshot that can help?

Body Language

Client De-escalation

Remember these 8 steps when addressing an upset client.

Find privacy

Once a situations heats up, suggest a private place to continue the conversation. Moving to another room gives both parties a bit of time to reset and prevents a client from feeling watched and judged by strangers.

Collect yourself

Remind yourself of your intention to be helpful and acknowledge that there are at least hundred possible solutions to whatever issue is at hand. Plant your feet into the floor. Push your shoulders down. Take a few deep breaths and focus on building a relationship, not arguing. Lower your intensity and sink into your normal vocal register. Provided you genuinely want to help, the client will see your sincerity and end up lowering her intensity to match yours.

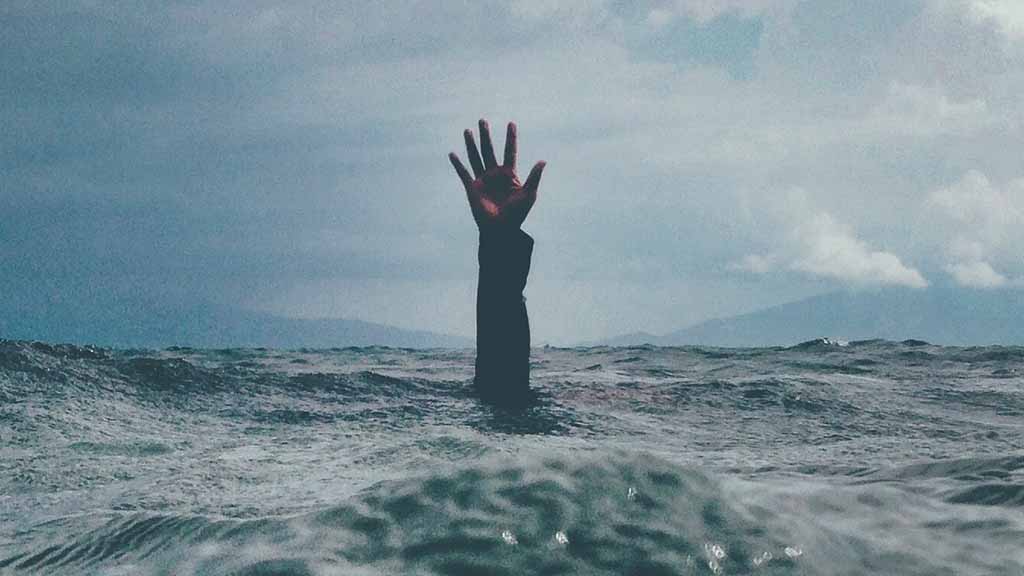

Recognize that anger is often a cover up for fear and sadness

Angry people are often sad people; people that shout often feel like crying. Seeing clients with this kind of X-ray vision helps you to understand them as they really are: not as monsters, but people who feel outsized by the problem at hand. Seeing clients in the context of their feelings, not their bluster, helps you to be more sympathetic.

Listen, acknowledge the client’s feelings, and allow her time to speak

Though a client’s emotions or reactions may seem over the top, try to focus on the pain and frustration she is feeling and acknowledge, both to her and yourself, that whatever she is feeling must feel lousy. Let her speak her mind. Talking to someone that she believes cares validates her feelings. Often times, that alone goes a long way in making matters better. If you feel as though you can’t listen with compassion, pass her to another co-worker or manager who can. Genuine concern for the aggrieved person maximizes the chances of success.

Don’t blame

Skip over any part of the story that requires someone to be blamed. Blame is a conversation stopper. Instead, quickly agree that you are both unhappy with the client’s dissatisfaction and that you both are interested in finding a fair solution.

Be direct

Remedy’s are best administered by a confident hand. Once you have heard the other’s side, be thoughtful about matters and make a strong recommendation for a next step, even if that step is to take a break and for everyone to spend more time thinking things through.

Take a break

If you feel that you are starting to anger, ask for a break. Even a brief trip to the bathroom or a chance to grab two cold bottles of water may be enough time to give everyone the reset they need.

Problem solve only when the client has calmed down

The loudest complainers don’t want a solution, they want to be heard, heard and understood. So do that. Listen and acknowledge. Then, after the client has started to regain her composure, suggest a solution, but keep in mind that in these situations, you have the power. A client may agree to a solution merely because she is intimidated to argue any further or feels that the chances of being heard and understood are hopeless.

I’m only half kidding when I say that your body language should mirror that of this dog. This animal needs no words to express his interest in what you have to say, his entire body is loudly articulating his interest in your next words and thoughts. When you go into room to talk to a client or an employee, does your body posture support or belie true empathy and an interest in learning more? The following body positions signal that your are interested and ready to listen:

- Eye contact, unless the person is angry in which case you should avoid long eye contact. Instead adopt a focus downward that suggests you are carefully listening.

- Body at a slight angle to the person if the person is angry, otherwise shoulders should be squared off to the individual.

- If you are standing, place one foot in front of the other.

- A slight leaning in

- A firm handshake

- Stillness

- No crossed arms or legs

- Use sitting or kneeling to convey a willingness to be of service, but only if the client wants to sit. If the client stands or if you want to communicate authority, stand.

Conversely be observant of the other party’s posture. Have they taken a corner position in the room, are they slumped in their chair or reluctant to make eye contact?

Most people are conflict averse. Many clients are intimidated by older, male doctors. Be on the alert for signs that the other party is uncomfortable. It won’t do anyone any good if the other side is so scared that they can’t feel or think. If you’re concerned that the other party will be intimidated by a private meeting, invite them to bring a friend. You too can ask if inviting someone into the conversation would be acceptable. You may want a third party present as an objective onlooker, to bring them along to learn themselves how to handle such conversations, or to give you feedback when the meeting is through.

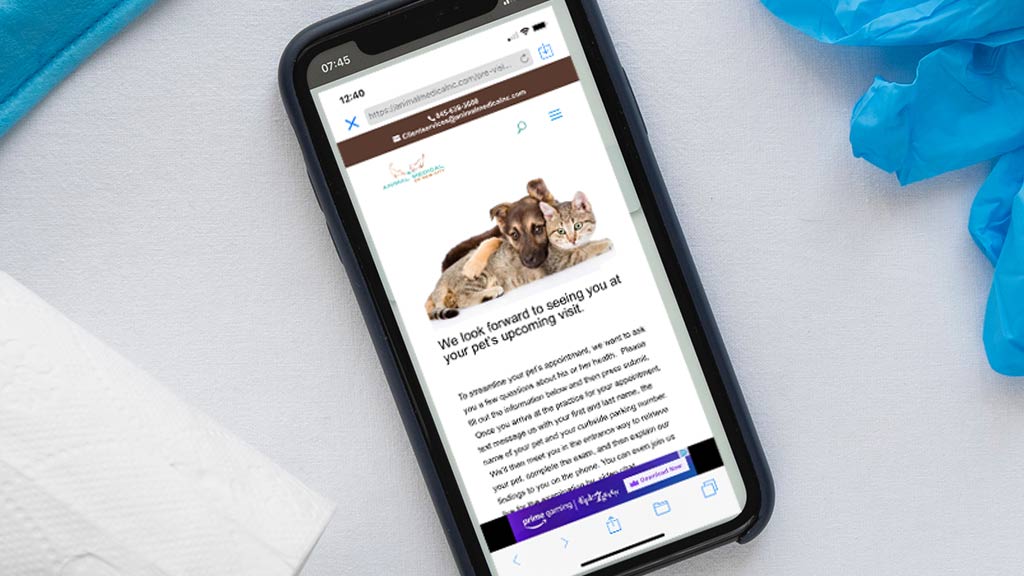

Dr. Mary Gardner On Helping Grieving Clients Focus

Coaxing pet owners to think about specific aspects of their pet’s health is an excellent way to draw them into conversation. An elderly patient can have ten things wrong with it, but zeroing in on one medical issue that pet parents believe is most significant helps clients to focus and is a great portal to doctor/client trust.

Dr. Mary Gardner of Lap of Love uses this technique every day in her work with her geriatric patients. As she explains:

“In caring for aged pets, you can sometimes encounter a patient with several obvious issues. Our inclination is to deliver this news and then to tell them all of our recommendations, but in our eagerness to help, we may be missing how the family sees the situation.

“Before you formulate your treatment plan, ask the family, ‘Tell me what is most important to you about the ailments you are managing with Rusty?’ This kind of question invites the client to be more specifically reflective. It can help them push past their general anxiety about many health issues and target one thing that everyone can agree should be addressed. It’s a start to treatment; it makes the client feel invested in the pet’s treatment plan; and it builds doctor/client trust.”

Over the years, Gardner has crafted some questions to help clients focus their attention on what they believe is their pet’s most critical health issue. Here are her favorites:

-

- What are your biggest fears about the future with your pet’s health?

- What are your most important health goals, should your pet’s health condition worsen?

- What abilities are most critical to your pet’s life; abilities that you can’t imagine him, or you, living without?

- If your pet becomes sicker, what do you need from me to help you decide if we should try for the possibility of more time?

After Gardner explores these thoughts in conversation with the pet owner, she draws the discussion to a close with a statement like, “I believe that I understand what your goals for your pet’s health and quality of life are. Based on that, this is what I recommend that we do.”

Inside the Conversation

Inside these conversations, there are usually five major stumbling blocks.

Goals

That’s not a typo. Having any other goal going into a potentially heated discussion, other than to learn and to build a relationship, is a mistake. Going in with goals means that you already know all the facts, that you have already made up your mind, and that you are closed off to listening. Try to walk in with an open, not closed mind, as to what the outcome of this meeting may be.

Blame

It took me awhile to let go of the need to assign blame, especially if I was trying to ‘fix’ some kind of employee issue. My logic was, ‘if we don’t figure out who did what wrong, we won’t be able to move forward with a solution,’ but experience has taught me that blame is not a conversation starter, but a stopper. It puts the other party on the defensive and pushes both parties into opposite corners of a fighter’s ring.

It’s so commonplace for us to assign blame for the problem before we attempt a fix, that it’s likely you’ll have to give this concept more thought before you act on it or even believe in it. But I’ll give you an experiment that is sure to make a convert of you: The next time something goes down with your spouse or kids, attempt a remedial conversation by first assigning blame. Compare that approach to a second where you agree that something went wrong and sharing how everyone participated in the unfolding event. You’ll find that where the first example encourages entrenchment, the second broadens perspective and thinking.

Not Knowing What You’re Feeling

There’s a reason that you’re keyed up about this meeting. You should explore it in depth. Understanding what you’re really feeling and why will help you identify what you’re experiencing inside the meeting when tensions begin to rise. Having explored these thoughts before you walk into the room will help you manage them better when you’re inside the meeting and facing them again.

Having Your Identity Challenged

Most of us believe (or hope to believe) that we have value; that others believe we are smart, kind, honest, trustworthy, well-intended, skilled, or experienced. This sense of identity, that others think of us a uniquely relevant, good and worthy of respect, is critically important to how we feel about ourselves. If people push on these notions, we push back.

Identity issues are the toughest hurdle to clear in a heated discussion. If others challenge your sense of who you are, or worse, if you challenge the other party’s sense of self, you’re at serious risk of things turning explosive.

Fortunately being aware of this risk may be enough to help you steer clear of such pitfalls. Just trusting that the very best parts of you can’t be eroded by one meeting or one person may be enough. To protect the other individual, avoid words or body language that could be perceived as disrespectful.

Lecturing

Be wary of any lecturing tendencies on your part. Lecturing signals that you know it all and that you are closed off to listening. Both are turn offs to the other side who may be earnestly looking for understanding.

Other Tips for Success and How To Close

Listen!

Novices worry about what they’ll say; pros focus on what they’ll hear. Your job is to watch the other party, put their words in context with their expressions, and look for opportunities to help them say what they need to say.

Be Direct

Some of you have been trained to deliver bad news in three parts: say something nice, then deliver the bad news, and then say something nice again. Detractors call the strategy a s^&t sandwich and I tend to agree. Over the years, I’ve seen this recipe served up at many veterinary HR offices. My take is that employees smell this meal coming a mile away. Don’t do it.

An honest tale speeds best being plainly told, as the saying goes. Say what you need to say in a civil, respectful manor. The other party will appreciate your candor and view it as a sign of respect and honesty.

Assume the Most Generous Explanation

A helpful way of shaping your attitude and line of questioning inside the discussion is to assume the most generous reason for the other party’s actions or position on matters. Indeed the reasoning behind their behavior is almost always more innocent than the picture that we have painted in our minds. Assume that the reason you are in this room together is no one’s fault, it will help you adopt the right mindset and tone.

Be Transparent

It’s not helpful if you assign blame, but it may be very helpful if you are honest about how you may have contributed to the situation.

Admitting medical errors is a dilemma for some of us for all the obvious reasons. I’ll leave you to decide what you believe is right for you and your business, but I want to share an observation that I’ve made. When supervisors ask medical teams to lie about hospital errors, they teach employees that there are some mistakes that can’t be admitted. Businesses that cultivate a sense of shame about mistakes strangle their team’s ability to learn, grow and improve. It distances leaders from employees and isolates owners from everyone in the building.

Don’t Try To Control The Person’s Emotions

Some people cry. Some yell. Trying to control another’s emotions in addition to staying on course with your line of thinking is overly complicated and controlling. Who’s to say that crying isn’t warranted? Who’s to say that yelling is bad? Rather than trying to bottle the other side up, you’re better off holding a course of empathetic, active listening. Remain alert and at the ready to restart the conversation once they’ve regained composure.

Take a Break

Even a pause to use the restroom or get a glass of water may be all everyone needs to regroup and have a reset. Formal or informal, asking for a break almost always works to give both parties another chance to connect.

An In-person Lunch and Learn For Your Team?

It can probably be fully funded! Find out how you can bring a fresh perspective and a lot of inspiration to your next team meeting! Click for more info.

Click a box below to explore more about these tough topics.

Grief

Stop!

I know how much all of love to multitask, but managing a grief discussion means we need all hands on deck when it comes to focus. Put your phone down, stop looking things up in the computer, and be present!

Knock off the baby talk

I know you mean well, but what’s behind that baby-talk squeal in your voice when you say, “Oh my god, I’m so sooooooooorrrryyyyy”? My sense is that it’s an extension of your own anxiety, but grieving people don’t need the responsibility of helping you with your anxiety, they have their own to manage. Your regular register of voice is a better choice.

I have been through this myself

I know that you’ve been trained to not say, “I know how you feel.” My experience has been that team members who have had similar pet experiences as those of the client can and are more willing to relate. Whatever you choose to say, don’t shy away from telling the client how their story is meaningful to you. It could be a gateway to trust and dialogue.

It doesn’t make it better if God has willed it.

Don’t use phrases like, “He’s better off, he was suffering so.” or “It was his time.” Many people don’t want their grief shut down because some higher power is in charge. Regardless of what the Universe may have planned, grieving clients need to be heard.

Watch for cues

The grief stricken are at their most vulnerable. They might not know if they need to talk or what they might want to say. Be on the alert for cues that the other party wants to talk. Once I was on hand to watch a veterinary pro observe a client wistfully look at a toy that belonged to her dog. The vet pro picked up the cue immediately and said. “I remember that you told me that was the toy that Benjamin always took with him on your hikes. Where did you go together?”

Her comment was in context of what the client was thinking and was genuine. Immediately the client told several stories about the hikes she and Benjamin had. The two seemed to be genuinely sharing a moment of real understanding and it appeared to be highly therapeutic for both.

Employee Tensions

Everybody Wants This To End

Most of the disagreements that I have brokered between hospital leaders and employees have been simmering for a long time. I find that both sides are often so entrenched in their position that they’re convinced that the other side is wrong and plain out to get them.

This is almost never the case. As an outsider coming in, I discover that both sides have reasonable positions. The problem isn’t that one is side is unreasonable so much as it is that both sides are so keyed up, that each is blinded to the other’s point of view.

However, there’s one thing that both parties always agree on: they wish they could put the disagreement behind them.

When you’re sitting down with an employee that has had a long standing disagreement with another, recognize that both parties need to be acknowledged and everyone wants things to be resolved.

Get Perspective

A very helpful thing you can do before walking into a meeting with a disgruntled staff member is to think of the most generous reason for their behavior. It will put you in the right mindset to be empathetic, forgiving, and ready to listen.

.

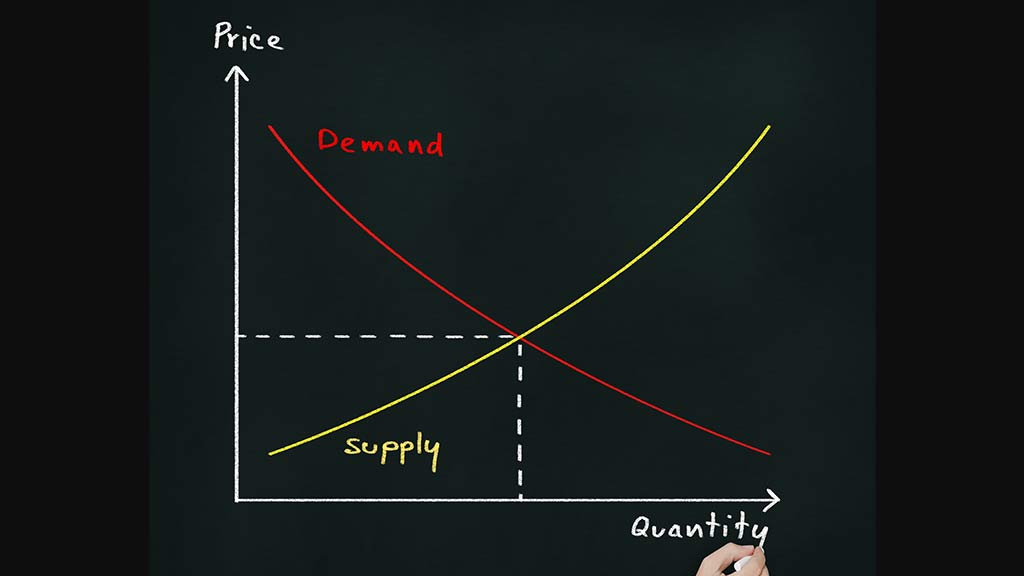

Financial Issues

Don’t send a child to do…

Many of our team members are young, so young in fact that they have never faced paying a veterinary bill costing thousands or even hundreds of dollars. It’s also safe to say that no 40+ year-old adult has ever asked them for help figuring out the financing of a large veterinary bill. Is it any wonder that in the absence of a lot of experience and training, these conversations often end up sounding cringe worthy?

After watching hundreds of these kinds of conversations, my sense is that young people who have had a chance to repeatedly trail more experienced team members are the ones that most adroitly handle questions about money. Don’t pull any punches when it comes to offering all your staff repeated exposure to and discussion about what everyone thinks works best when discussing client finances.

Review your financial policies

It’s probably been a couple of cycles of hires since you last had a group-wide pow-wow on what your credit policy is and what third party tools your practice offers to help clients pay their veterinary bills. For my part, I believe that every practice should be up to date on the latest offerings of CareCredit and Vetbilling.com.

Explain the ‘why’ of the treatment plan

If a client expresses a concern about cost, reexplain the reasoning behind the treatment plan as it stands. The conversation might sound something like, “Okay Mr. Halow. I understand that you want us to come up with a less costly treatment solution. I understand and I’m going to help you. Let’s start out with what this treatment plan accomplishes for your pet and why I opted for it based on our conversation and my examination of Bingo. From there, you can tell me what you want most for Bingo and then we’ll figure out other options to address the rest of his health concerns. We have lots of medical options we can explore as well as some financing options, so trust that we’re going to figure this out.”

Never make a recommendation without a reason

Too often I see services on estimates that are explained away as options, “This is a vaccine that we recommend for all dogs that go to boarding facililities. We put it on the estimate in case it’s something that you want.” When you discuss veterinary services like this, you downplay their value; it’s the veterinary equivalent of, “Since Bingo is getting the turkey special today, he can also get a soup or salad. Would you like either of those?”

During an examination, we veterinary professionals spend approximately 10-20 minutes asking clients about the pet’s history. We should be using that information as a foundation for what we think Bingo needs. Never say things like, “And we have a blood test that we can do prior to the surgery to make sure Bingo is healthy enough to undergo anesthesia. Would you like that?” Instead phrase the recommendation this way, “Based on Bingo’s age and breed, Dr. Johnson recommends that we do a pre-anesthetic blood test. It will ensure that Bingo is healthy enough to undergo anesthesia.” The former phrasing makes the service sound like an up sell; the second phrasing sounds like we’re paying specific attention to Bingo’s needs and making a recommendation pointedly for his benefit.

Angry Clients

Try a FearFree approach to clients

A cat comes into the clinic and tries to bite and claw you. Do you fire him? Why then, don’t we extend the same objectivity and compassion to our clients when they too bare their teeth? Aren’t they stressed out as well? Don’t they have their own fears about money, the pain their pet could experience, and so forth?

Since the Pandemic, we’ve lost our patience with clients, but I think it’s an important quality for us to reclaim. I know they can be bossy, I know they can be demanding, rude, and disrespectful, but I also know that we are seeing them at their emotional worst. If they were a cat, we’d try a creative approach to getting close before reaching for the Telazol, and I think we should extend the same courtesy to them:)

In the end, a team-wide effort to outwit our clients’ gut instincts to act out will ultimately be more satisfying than firing them. And to be clear, approaching clients with compassion isn’t rolling over and taking it; it’s representative of our broadness of mind, altruism, and intelligence. It’s the same kind of behavior that you would hope to see in the wisest of teachers, those that can see past the bully, the class clown, or the chronic absentee to the hurt individual underneath, and then offer some genuinely effective remediation.

Pass them off

Regardless of our best attempts, some clients get under our skin at which point we are ineffective at dealing with them. In these cases, it’s best to pass the client off laterally to another coworker. Say something like, “I’m not helping you effectively; may I ask my coworker to assist us both? She’s very experienced and It think she’ll be able to help.” Then excuse yourself and get your colleague.

This tactic usually works. Eager to show her talent, and pleased you’ve place your trust in her, this employee will usually come to the situation with fresh energy and a strong interest in making things right.

.

Compliance

Start with the ‘Why’ that is specific to the client’s needs.

Always ensure that you have listened to the client’s needs before starting the exam, then frame your healthcare recommendations inside the context of what the client wants to achieve for his or her pet.

Stories work better than education

People are more likely to understand and to be moved by the story that made a believer out of you. Tell the story of why you are making the recommendation, not the science.

Step towards the client that shuts down

I once observed the following exchange in an exam room.

Doctor: “Have you considered a tick preventative?”

Pet owner wife #1: “Oh yes, we need that. I hate when I see ticks!”

Pet owner husband #2: “We don’t need that. I never see ticks on Rufus.”

The conversation came to a screeching halt. The doctor feebly attempted to give the wife education on tick medication, but she was already sold. The doctor needed to talk to the husband, but he appeared shut down, so she let it slide.

I don’t think we should retreat from these situations, but step towards them. To not do so allows an uncomfortable mistrust to linger in the air and spoil the examination for everyone. Next time something like that happens to you, try this formula:

- Validate the pet owner’s perspective: “I see how you would believe that ticks are not an urgent matter, especially if you’ve never seen one.”

- Share your vantage: “I see tick issues here frequently enough that I don’t feel like I’m being of the best service if I don’t share my perspective.”

- Remain helpful: “If my recommendation for the medication isn’t right for you, I’ll be happy to give you other ideas. Tell me any other thoughts you have about tick prevention.”

- End with no pressure: “Thank you for letting me share. I want to be the best I can be for your visit today. Any time I provide care, don’t hold back any concerns. I love this work and want to be of help to your pet and you.”

This kind of exchange takes the tension out of the air and lays a foundation for a more trusting relationship moving forward.